Should we abstain from voting? (In nondeterministic elections)

Looking at the "polluting the polls" argument in the context of probabilistic voting

Polluting the polls

Philosopher Jason Brennan argues in his paper “Polluting The Polls: When Citizens Should Not Vote” that most people should abstain from voting. The argument boils down to the view that most people are not informed enough to vote well, and so should therefore not vote lest they “pollute the polls”.

The other political philosopher that writes about our duty to vote, who is also named Brennan, has argued that we don’t have a (positive) duty to vote, because the odds that our vote will make the difference in an election are so astronomically low. Which is true, the chance that your vote will be the one that tips the scale either one way or the other is negligible.

This can be used as a counter argument. If the odds of causing a positive outcome are low enough that it makes no practical difference, the same can be said about the odds of causing a negative outcome.

Nondeterministic elections

I’ve been thinking about this because I’ve been analyzing “nondeterministic” voting systems. These are voting systems that use an element of chance. So you might be familiar with some different voting systems, such as Plurality Voting, Approval Voting, Ranked Choice Voting…

Even though there are many different voting systems and some have much better theoretical properties, most systems used in practice are deterministic. This means the election result depends basically only on the votes cast (although in case of ties, a deterministic system might use a coin toss or similar random method just to break the tie).

In contrast, nondeterministic voting systems use chance for more than just breaking ties. The simplest example is the ‘Random Ballot’: each voter submits a ballot, and one ballot is randomly drawn to pick the winner.

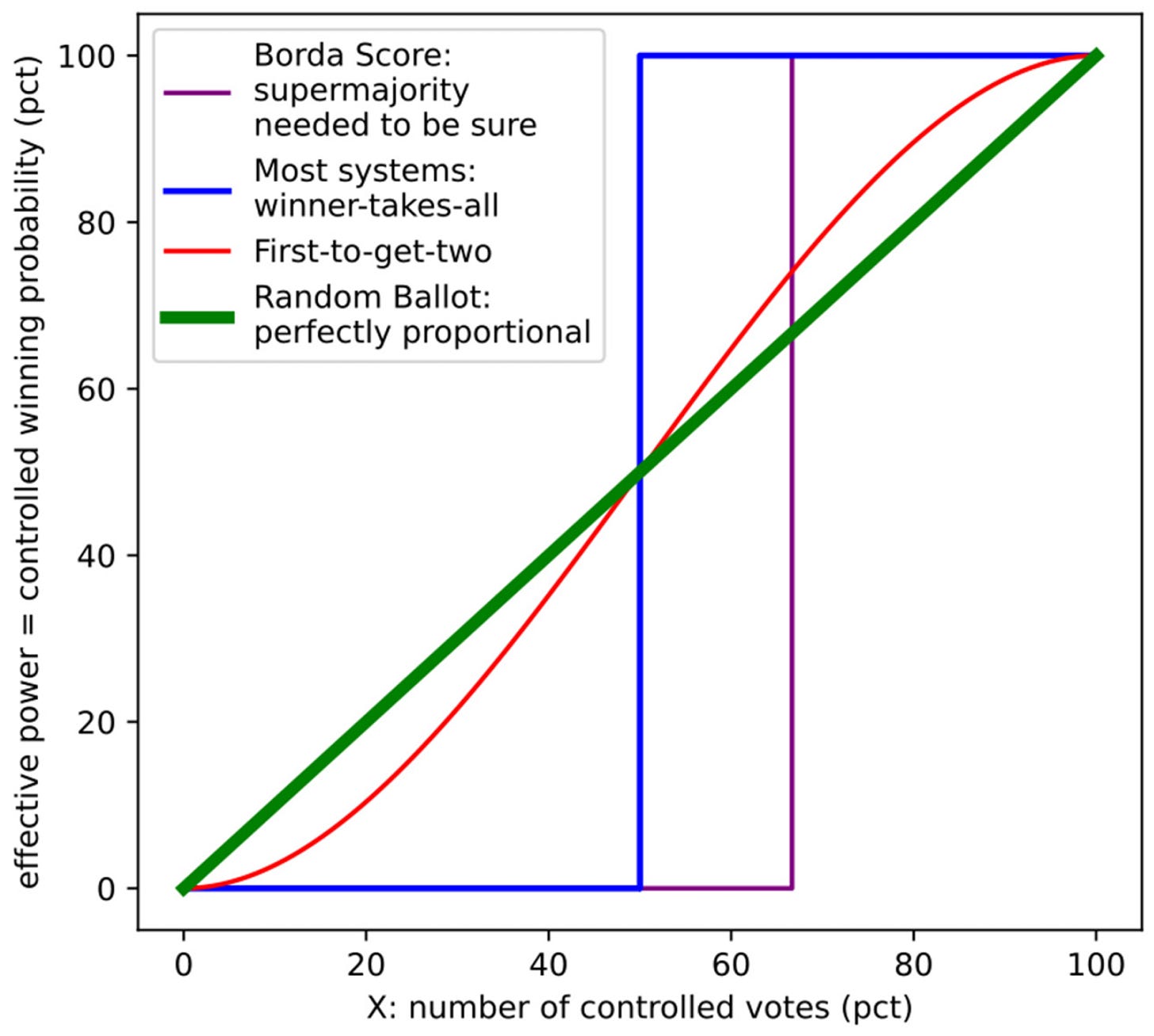

One attractive feature of non-deterministic systems is their ability to reduce the ‘tyranny of the majority’. In most deterministic systems, controlling just 51% of the votes gives 100% power, leaving the other 49% with none. Some deterministic methods need even more than a simple majority to ensure a win: for instance, with the ‘Borda score’ system, you need two-thirds (a super-majority) of the votes.

With the ‘Random Ballot’ system, having 51% of the votes only gives you a 51% chance of winning. Any group’s share of the vote directly translates to their winning probability, making the distribution of power perfectly proportional. Historically, nondeterministic systems can be traced back to ancient Athenian democracy, where officials were chosen by lot to ensure equal participation and prevent the concentration of power.1

Not all non-deterministic systems are perfectly proportional. For example, in a method where ballots are drawn one by one until two ballots for the same candidate are drawn, the effective power of a group controlling X% of the votes would lie somewhere between the perfectly proportional 'Random Ballot' method and the step-function of most standard systems. This relationship can be visualized as a function:

For most winner-takes-all systems (conventional voting systems) it is a step function; if you have 51% of the vote you are in power 100% of the time (blue line). The random ballot (green line) is perfectly proportional (49% votes = 49% in power), and the method of drawing ballots until you’ve drawn the same candidate two times is somewhere in between (red line).

In a future blog post I will look at the (positive) arguments to vote in nondeterministic elections (which will be based on my paper on the subject), but for now I will tackle one concern with nondeterministic voting systems:

If they increase the influence of the average voter, doesn’t that increase the strength of the “Polluting the polls” argument from earlier?

Indeed it does, in an election where the average citizen has more influence, they also have more opportunities to create adverse outcomes. If we want to refute the “polluting the polls” argument in nondeterministic elections, we will need a different argument.

Polluting the polls and minority groups

One issue with Brennan's argument is that it seems to suggest that minorities shouldn’t vote. Those who are least educated, and therefore (according to Brennan) should abstain from voting, often belong to disadvantaged groups, like the poor and minorities. Discrimination and lack of opportunities can limit their education, so they would be the ones who disproportionately have to refrain from voting.

Brennan acknowledges this but argues that while minorities have been poorly served, advocating for better education and opportunities doesn’t mean they should vote as much as other groups. He compares this to professions like surgery or law, where unfair advantages due to discrimination should be fixed by improving education and opportunities, not by allowing unqualified people to work in these fields. Brennan argues that allowing politically ignorant people to vote is similar. If minority groups are predominantly politically uninformed because of discrimination, efforts should focus on improving their situation rather than pushing them to vote, which might lead to bad decisions.

But is this such a good idea? If a minority group tends to abstain from voting, won’t the government simply ignore their needs? While Brennan suggests that educated experts could advocate for these communities, this is questionable. Many experts might prioritize other issues, and people usually understand problems that affect them directly better. So, if minorities disengage from voting, their concerns will probably be overlooked.

Is this level of knowledge feasible?

Another issue with Brennan’s argument is practicality. Getting the level of knowledge he thinks is necessary for voting seems impossible. General elections involve a wide range of topics like defense, taxes, healthcare, housing, crime, transportation, international relations, education, and a whole lot more. Even if you’re well-educated in some areas, you’ll be ignorant in others. It raises the question: Do you need to be an expert to vote, or is some level of knowledge enough? If so, where is the line?2

This becomes especially worrying if we remember the existence of the Dunning-Kruger effect, which shows that people who lack competence often overestimate their knowledge, and vice-versa. If people followed Brennan’s advice, those ignorant of their lack of knowledge would keep voting, while well-educated people might think they’re not competent enough and abstain. This could result in a less-informed electorate, with more ignorant voters continuing to vote due to their overconfidence, while the educated abstain.

Conclusion

Because of these issues with practicality and minority disenfranchisement, I don’t find the “polluting the polls” argument very convincing. Which means that if we want to undermine the reasons to vote (in nondeterministic voting systems) we will need other arguments. I will look at some of these arguments in a future blog post.

Modern citizens’ assemblies, randomly selected from the population, are a similar concept.

This argument doesn’t work if you can direct your voting power to your area of expertise, like I proposed in my department voting post.

People keep reinventing Jim Crow and thinking they’re being original

Given how much of an influence self interest and motivated reasoning has on actual people, suggesting that most people should not participate in elections is pretty much guaranteeing an outcome where gobernment doesn’t actually care very much about most people, which appears likely to be bad. Also given how knowledge tends to be correlated with caring more about politics and how people who are more invested in the outcome tend to have more influence due to a number of reasons like participating actively in lobbying and activism, and the usual reasons around concentrated harm and benefits, and the fact that experts already have quite a bit more influence than any individual voter even before you take note of institutions like the federal reserve that are basically run by technocrats, and the fact that most low engagement citizens who don’t vote already tend to be low information citizens, this looks like it is at major risk of trying to solve an already solved issue and over-correcting in the opposite direction..

That said the biggest logical problem with the paper is that anyone knowledgeable enough to be familiar with this argument is also almost certain to be knowledgeable enough that they would actively add information to an election, since they would be far more knowledgeable than the usual voter. So even if you ignore just how badly it went when people tried actually implementing similar policies and accept the argument’s premises, the argument still doesn’t make sense on its own terms. You can try to construct a steel man of this argument and point to similar practises that everybody supports, but I think the logical problem I just pointed out is simply an unsolvable issue for this argument.