Worker cooperatives are firms that, unlike traditional firms, are run democratically. This means that instead of the owner of the firm deciding who manages the workers, the workers become part owner and get a say in how the firm is run. This has some advantages, such as workers working harder and productivity appearing to increase.

Wait… how’s that even possible in theory?

You might be asking yourself: won't workers become lazy since the profit is shared with their colleagues, which means they only get a small proportion of the fruits of their individual labor? According to the free-rider hypothesis, rational and self-interested agents will always have an incentive to put in less effort and be a parasite to the efforts of others. That’s literally the first lesson of game-theory 101.

Yes, but this is solved by the second lesson of game-theory 101: repeated interactions. Once you can build up relationships with people, you get a chance to punish free-riders while rewarding the helpful. Not to mention, we’re not the self-interested rational agents of game-theory 101. We’re complex, we care about cooperation and kindness and all that other icky stuff.

It’s not just the behavior of humans that’s wrong in the game-theory 101 model. These simple economic models assume perfect information which, in reality-land, managers of traditional firms do not have access to. According to economist Friedrich Hayek, top-down organizers have difficulty harnessing and coordinating around local knowledge, and the policies they write that are the same across a wide range of circumstances don't account for the "particular circumstances of time and place".

One study, that looked at real firms with high levels of worker ownership, found that workers there start checking each other’s work more, which makes those workers more productive than those with low- or no worker ownership. This knowledge of what everyone is doing is also not going to waste, since the workers can steer the direction of the company bottom-up through their votes.

Those who make the top-down policies in a traditional company are different from those who have to follow them. In addition, those who manage the company are most often different from those who own the company. These groups have different incentives and accumulate different knowledge. This means that coops have two main advantages:

Workers can harness their collective knowledge to make running the firm more effective.

Workers can use their voting power to ensure the organization is more aligned with their values.

…But also… these game-theoretic arguments strike me as putting the cart before the horse. We observe that people work harder in coops. I agree that the math of the economics-101 model is very pretty, but that shouldn’t be a reason to disregard our observations. If the model contradicts the data, we throw out the model.

Could this be selection bias?

Could it be that workers who are more motivated to work harder for a coop, are also more likely to start or join a coop? This would mean that we can’t use them as a measurement of how ‘normal people’ would perform in a coop.

If we only had observational studies this would indeed be a concern, but we’ve also tested this experimentally and found the same increase.

Okay, but what about firm productivity? You can’t easily test that in a lab, and it’s possible that while the workers are more productive, the firm itself isn’t.

That would be strange, but yes, it’s possible. Studies show that the cooperative firms themselves are also more productive, but these studies are indeed not done in a lab so could be subject to selection bias. Plus the effects are small and there are some studies that don’t show this increase. However, even if we revert to the null-hypothesis that they’re about equally as productive as traditional firms, the question would remain… where are they?

Why aren’t there more worker coops?

Here’s an old economics joke you might have heard before: Two economists are walking along the sidewalk. One sees a five-dollar bill and bows to pick it up. The other says, “Don’t bother, if that was a real five dollar bill someone else would’ve picked it up already”.

This joke is making fun of the assumption of perfect information. Unlike in the simplistic models, in the real world, market participants do not have all the necessary information. If you were to ask a random American what a coop was and how it worked, do you think they’d be able to answer that accurately? It takes time for innovations to spread. And we do observe that the number of coops are increasing rapidly, e.g., the number of worker coops in the US has tripled in the last decade.

So maybe a better question is: why did it take so long?

It could be that legislation constrained coops. Or maybe it’s because traditional firms have had more time to improve. There are, according to my research, approximately 4.7 bazillion books on how to run and manage your firm effectively while there’s less than 0.001 bazillion books on how to do the same for coops.1

It could also simply be good old-fashioned propaganda that made people wary of collectivization.

I think all of these play a role, but I also think there’s another, more straightforward answer.

Return on investment

Capitalists tend to not like coops. You might object that capitalists only care about efficiency, so they would embrace coops if they were indeed more productive, but that’s not actually the case. Capitalists care about profits, which is not always aligned with productivity.

Say there’s a startup coop that can turn $10 of investment into $100, but will split that $50 with the workers and $50 with investors. Meanwhile there’s also a traditional capitalist startup that can turn $10 into $90 which goes purely to the investors. In this case the coop is more productive, but the capitalist firm gives the capitalists a higher return on investment, meaning the investors will invest in the capitalist startup even though it's less productive.

On top of that capitalists have less power over coops. Since workers have more protections/decision-power, capitalists aren’t micro-kings and have to actually work together with the workers, which is annoying.

The return on investment for society may be larger (especially if we take into account all the costs traditional firms externalize to society at large that cooperative firms internalize) but that doesn’t mean they have a higher return on investment for investors.

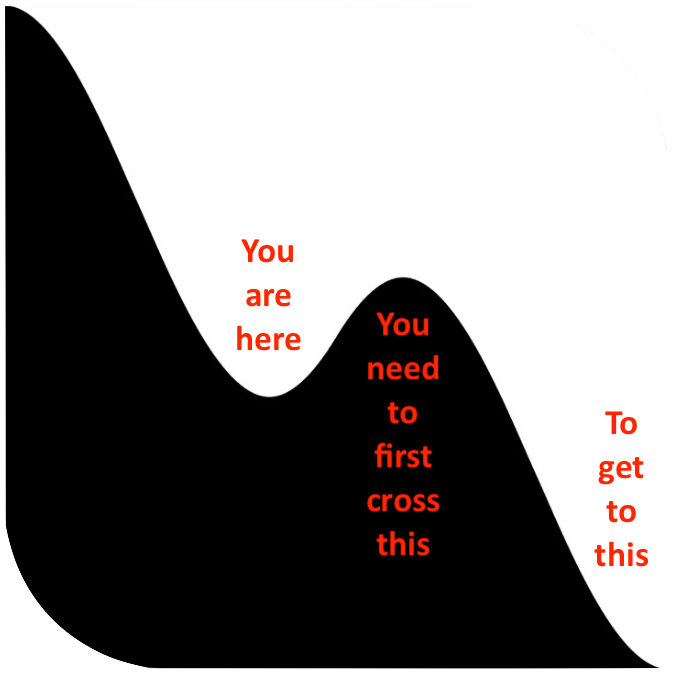

Studies show that capitalist firms do better with more capitalist firms around, while coops do better with more coops around. So we have a bit of a lock-in effect. It may be that to get to a place of greater long-term productivity we first need to give coop firms some time to find their footing.

How worker co-ops can help restore social trust

The US is experiencing a great decline in trust. According to the US General Social Survey, people who agreed with the statement "most people can be trusted" went from 49% to 25% between 1984 and 2022.

This post is partially based on an earlier post of mine, published on the EA Forum, which was in turn based on the work of economist Cahal Moran.

I know nothing about running a firm, but even I can see areas where coops could readily improve: e.g., coops are currently not using the state-of-the-art in voting theory. With better voting mechanisms the cooperation/coordination within the firm could drastically improve.

It’ll probably take some time for coops to catch-up to this head-start in firm design that the capitalist firms have.

Interesting! However, I'm skeptical about the marginal productivity of worker co-ops over incentive pay. It can be tricky to distinguish between the two because worker co-ops almost always intrinsically implement a form of incentive pay, that is, the worker's pay varies with the firm's performance, whereas in many traditional capitalist firms, salary is fixed. Economic theory *can* predict that certain compensation schemes have free-rider problems, but other compensation schemes---especially pay for performance---do not. In fact, one of the most popular models today (principal-agent) predicts that pay for performance is optimal, group bonuses are good, and fixed salaries are worst.

This has created another mystery: why the heck do so many companies pay fixed salaries? It's probably because of risk aversion. People like having a consistent salary rather than getting paid $0 today and $250,000 in two years. (And that seems like a reason that might apply to worker co-ops as well.)

Anyway, the empirical evidence on worker co-ops productivity is not particularly convincing to me for this reason. For example, the experiment you cited cannot distinguish this because it compares a group that votes on its compensation contract to a group that does not, but the only allowable compensation contracts are group bonuses or tournament pay rather than individual pay-for-performance. Of course we should expect the group that can vote to perform better: the group vote is *itself* mimicking a selection effect, where people vote for the incentive contract they know will motivate themselves. If you as a manager in a capitalist firm knew your employees well enough to know which compensation contract would work best, you could re-create this effect in a capitalist firm (note: I'm not saying there is selection bias; I'm saying that the experiment's average treatment effect is equivalent to a sort of selection effect in a natural environment).

Also, we (economists) don't really have a good understanding of organizational structure in general. Early organizational economics models predicted that managers are useless, and newer models don't do much better. We still have no idea why managers are everywhere! But that too is an empirical observation that we shouldn't ignore. Does it mean that hierarchical organizational structures are better? No. But it does suggest that cooperative structures have some major frictions that prevent their implementation, at least.

I think the answer is pretty simple: The people who work in coops are more likely to select for conscientiousness and other traits that correlate with being more-productive-than average. Another way of saying that is that they’re true believers. The other reason is that capitalist ownership likely scales easier than worker coops. It’s faster to make decisions, workers don’t need to put as much thought, there’s probably less bureaucracy and procedure. So even if the coops are 5-10% more productive when they hit maturity, it may be that it doesn’t take as long to reach maturity for more capitalist firms because the lack of egalitarianism streamlines the process.

Anecdotally, the people who care about co-ops in America are more likely to be, like, booksellers or whole foods-esque grocery shoppers. Working class people in my experience only want to own a business if they don’t want to be told what to do (I think there is social science on small business owners saying as much) and otherwise are very much just at their workplace to collect a paycheck. Heck, I’m not even a working class person and I wouldn’t want to be a co-owner at my hypothetical workplace. Too much responsibility. And yeah, there are low wage workers who’d generally benefit from more input and protections in the workplace, but I think if you gave them that, many of them would still not want to be owners, and many of them would still be lower productivity.