How Democratic Is Effective Altruism — Really?

A closer look at how reputation, funding, and influence shape EA discourse

Introduction

Effective Altruism (EA) is a social movement that aims to use reason and evidence to help others as much as possible. It encourages people to ask not just “how to do good”, but how to do the most good. This has led members to support things like global health interventions, existential risk reduction, and animal welfare.

I used to be closely involved in the movement, and I still think many of its ideas are worth defending. But as the movement has grown, so have certain structural problems: increasing reliance on large donors, pushback on dissent, and systems that concentrate influence in subtle but significant ways. This post is about those concerns — not to denigrate the movement, but to explore how it might better live up to its own stated values.

EA and conformity

One of the clearest places where these structural issues show up is in how the movement handles conformity and internal disagreement. Carla Zoe Cremer, a former EA insider, has become an outspoken critic of how EA functions internally. Back in 2020, she warned about “value-alignment”, her term for extreme intellectual conformity within EA:

value-alignment means to agree on a fundamental level. It means to agree with the most broadly accepted values, methodologies, axioms, diet, donation schemes, memes and prioritisations of EA.

Her concerns deepened in 2021, when she co-authored a peer-reviewed paper with Luke Kemp on existential risk studies — one of EA’s flagship cause areas. The paper argued for more diverse voices and warned that the field had become overly “techno-utopian” and was in need of democratic reform.

The reception was… rough. According to her:

It has been the most emotionally draining paper we have ever written. We lost sleep, time, friends, collaborators, and mentors because we disagreed on: whether this work should be published, whether potential EA funders would decide against funding us and the institutions we're affiliated with, and whether the authors whose work we critique would be upset.

While many in the community responded constructively, others reportedly sought to suppress the paper — not on academic grounds, but out of fear that it might alienate funders.1 The clear implication here is that critique is encouraged, as long as it doesn’t threaten the financial or ideological foundations of the movement. In response, Cremer laid out a series of concrete reforms to tackle this problem:

diversify funding sources by breaking up big funding bodies and by reducing each orgs’ reliance on EA funding and tech billionaire funding, it needs to produce academically credible work, set up whistle-blower protection, actively fund critical work, allow for bottom-up control over how funding is distributed, diversify academic fields represented in EA, make the leaders' forum and funding decisions transparent, stop glorifying individual thought-leaders, stop classifying everything as info hazards...amongst other structural changes.

She reached out to MacAskill and other high profile Effective Altruists (EAs) with these concerns. While they acknowledged the issues, Cremer didn’t think talking to them achieved much:

I was entirely unsuccessful in inspiring EAs to implement any of my suggestions. EAs patted themselves on the back for running an essay competition on critiques against EA, left 253 comments on my and Luke Kemp’s paper, and kept everything that actually could have made a difference just as it was.

EA and criticism

This story might surprise you if you’ve heard that EA is great at receiving criticisms. I think this reputation is partially earned, since the EA community does indeed engage with a large number of them. The EA Forum, for example, has given “Criticism of effective altruism” its own tag. At the moment of writing, this tag has 490 posts on it. Not bad.

Not only does EA allow criticisms, it sometimes monetarily rewards them. In 2022 there was the EA criticism contest, where people could send in their criticisms of EA and the best ones would receive prize money. A total of $120,000 was awarded to 31 of the contest’s 341 entries. At first glance, this seems like strong evidence that EA rewards critiques, but things become a little bit more complicated when we look at who the winners and losers were.

At the time, several voices — myself included — raised concerns about EA’s increasing dependence on billionaire donors, especially crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried. FTX, his company, was bankrolling much of the EA movement at the time.

There was skepticism of crypto, yes — but the deeper concern was about how much influence was being concentrated in the hands of the ultra-wealthy.

Those critiques didn’t win the contest. Instead, winning entries focused on comparatively minor problems within the movement. And then, just weeks later, FTX collapsed and Sam Bankman-Fried was arrested for fraud. Whoops!

So it seems like EA encourages criticisms, but mostly of a certain kind. Critiques that question technical assumptions or offer marginal suggestions are welcomed — even rewarded. But those that challenge the movement’s power structures, funding models, or social norms? Those are more often ignored, sidelined, or quietly punished.

Consider the 2022 contest again. Four of the winners chose to remain anonymous. One went even further, requesting that the entry be hidden from public view entirely. As Cremer put it a year before the contest:

If you believe EA is epistemically healthy, you must ask yourself why your fellow members are unwilling to express criticism publicly

She’s not alone. In 2023, a group writing under the name ‘ConcernedEAs’ published the now-infamous essay “Doing EA Better”. This essay critiqued the power structures in EA, and subsequently made both the “top 10 most valuable posts of 2023” and “the top 10 most underrated posts of 2023” on the EA forum. The authors explained their anonymity bluntly:

Experience indicates that it is likely many EAs will agree with significant proportions of what we say, but have not said as much publicly due to the significant risk doing so would pose to their careers, access to EA spaces, and likelihood of ever getting funded again. Naturally the above considerations also apply to us: we are anonymous for a reason.

And no, despite what people think, I wasn’t one of the authors. I’ve published basically all my criticisms of EA under my real name. For what it’s worth, I’ve never gotten any money from any EA,2 or gotten invited to give a talk,3 or anything similar,4 despite being heavily involved with EA for half a decade.5 In hindsight, I probably should’ve posted anonymously too.6

EA and centralization

Concerns about centralization in Effective Altruism aren’t new. Back in 2020, Cremer already warned that EA had quietly become a hierarchical ecosystem dominated by a small set of tightly interlinked institutions. In her words:

EA is hierarchically organised via central institutions. They donate funds, coordinate local groups, outline research agenda, prioritise cause areas and give donation advice. These include the Centre for Effective Altruism, Open Philanthropy Project, Future of Humanity Institute, Future of Life Institute, Giving What We Can, 80.000 Hours, the Effective Altruism Foundation and others. Earning a job at these institutions comes with earning a higher reputation. [...]

I’m not aware of data about job traffic in EA, but it would be useful both for understanding the situation and to spot conflicts of interest. Naturally, EA organisations will tend towards intellectual homogeneity if the same people move in-between institutions.

Since then, things haven’t improved much. In 2023, the Future of Humanity Institute was shut down by Oxford’s Faculty of Philosophy. No official reason was given, but the move followed a major public scandal involving FHI’s director, Nick Bostrom. It’s probably fair to assume Oxford just didn’t want to be associated with FHI anymore.

Meanwhile, several prominent EA orgs — including the Center for Effective Altruism, Giving What We Can, and 80.000 Hours — were brought under a new umbrella organization called “Effective Ventures”, which isn’t a great name if you want to avoid the impression that it’s all run by big funders. Maybe that’s partially why they decided to spin off the latter two again.

Job mobility data across these organizations is still unavailable, but a quick scan of LinkedIn seems to show what many insiders already suspect: EA is basically operating as a closed network. EAs often rotate between the same set of institutions, with reputational capital flowing through a handful of elite hubs in the US and UK. Take, for example, where EAs move to:

Despite EA’s claim to be a global movement, much of its leadership, funding, and research continues to originate from the US and the UK. And more specifically, a small number of cities, including London, Oxford, San Francisco, and Boston.

While this is slowly improving, the imbalance remains striking:

These charts don’t just illustrate where people work or move. They hint at where decisions are made, who has access to influence, and which perspectives are structurally overrepresented. In a movement that aspires to global impact, this kind of centralization isn’t just a practical concern — it’s an epistemic one.

EA and democracy

Effective Altruism presents itself as a pro-democracy, globally-minded movement for empowering the most amount of people. In practice, much of its influence rests in the hands of a few ultra-wealthy donors — most notably those from Silicon Valley.

Take Open Philanthropy, co-founded by Facebook billionaire Dustin Moskovitz. In 2022 alone, it donated $350 million to GiveWell-recommended charities — covering 58% of their total funding. The EA organization 80,000 Hours has received over £20 million from Open Phil, making up nearly two-thirds of its budget. They’ve also given millions to the Effective Altruism Fund, the Center for Effective Altruism, and to the Effective Altruism Foundation.

And that’s just Open Philanthropy, there are other big donors too.7

While there have been incremental efforts to diversify funding sources, the reality is that EA remains deeply reliant on a handful of individuals whose fortunes were made through systems of capital accumulation — systems that many of EA’s core institutions are hesitant to critique. As philosopher David Thorstad writes:

If there is one thing that wealthy philanthropists almost never do, it is to challenge the institutions that create and sustain their wealth. This is not to say that philanthropists are driven primarily by selfish motives, but rather that even the best of us find it hard to conclude that the institutions which created and sustained our wealth could be bad.

This reluctance becomes especially problematic when those very institutions — tech monopolies, deregulated markets, investor-driven innovation — are key contributors to the very problems EA claims to solve.

Thorstad continues:

In an age of rapid and devastating climate change, Silicon Valley is becoming an increasingly large contributor to global emissions. Most of the wealthiest contributors to effective altruist causes have been quite hesitant to take steps to address climate change, despite their own contributions to the problem.

More broadly, I think that the difficulty which philanthropists have in critiquing the systems that create and sustain them may explain much of the difficulty in conversations around what is often called the institutional critique of effective altruism.

This “institutional critique of EA” is the idea that EAs too often focus on alleviating symptoms rather than challenging the systems that produce harm in the first place.8 There’s a hesitancy to step into the realm of the political, perhaps because doing so would risk alienating the very donors who fund the movement.

And it’s not just a matter of self-censorship. Funding biases people towards the position of the funders — yes, even intelligent researchers.9 It’s rarely about outright bribery, it’s about distorting the beliefs themselves.10 As Upton Sinclair once put it:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

This is precisely why so many people — myself included — have called for democratizing EA institutions. Ideas have ranged from participatory funding, to mutual aid structures, and of course, I’ve always advocated for turning EA organizations into worker cooperatives. However, whenever I’ve suggested this I’ve always gotten strong pushback from the EA community.

To this day, none of the central effective altruists organization are organized democratically.

EA and voting power

The Effective Altruism Forum doesn’t use “likes” or “hearts”, it uses “votes”. Posts and comments with more votes appear higher, and those with fewer votes sink — a common feature in many online platforms. But here’s the twist: on the EA Forum, your voting power scales with your reputation, quantified as “karma” (the number of “votes” you have received).

At first, this might seem like a clever way to reward quality contributions. New users start with modest influence, namely ±2 points per vote11. But as others upvote your content, your karma increases, and so does your power. At 1,000 karma, you can cast ±6 votes. At 10,000 karma, you can apply nine votes at once. The theoretical cap? Sixteen!

Some might say that this is meritocratic: the most respected contributors get the most influence. In reality, it creates a feedback loop of reputational inequality. Popular users accumulate more power, which they can use to further amplify allies, bury dissent, and shape what others see, or don’t see.

That influence is invisible but immense. For instance, once a comment drops below –5, it’s hidden behind a “click to view” barrier and pushed to the bottom of the thread. On top of that, once your comment gets negative karma, it’s deleted from the frontpage.

A few downvotes — especially from high-karma users — can effectively hide a perspective from public visibility. And because the forum doesn’t display how much each vote changes a score, observers can’t tell whether a –10 represents broad community disagreement or a few power users disagreeing with you. The effect is the same: disappearance.

In theory, this design helps surface high-quality content and suppress spam. In reality, it fosters a subtle but persistent form of soft censorship.

Dissenting views vanish before gaining traction.

Authors self-censor for fear of reputational loss.

Karma becomes not just a signal of contribution, but a gatekeeping mechanism.

And this system has only become more prominent over time.

It used to be that when you hovered over a user it showed you their contributions: wiki edits, comments, sequences… but not karma. Today, most of these are gone and karma has taken their place: with a bigger font, with more color weight, and shown before any other metric. Even the subtle UI changes reinforce the message: karma is who you are here. There’s even a new icon that flags users with low karma, nudging readers to take their posts and comments less seriously.12

This isn’t just a technical issue. This is a design philosophy — one that rewards orthodoxy, punishes dissent, and enforces existing hierarchies. You can downvote someone into silence. You can upvote someone into authority. And over time, that shapes the information landscape.13

The EA Forum is the movement’s central discussion space. Its architecture shapes what ideas emerge, which critiques survive, and who gets heard.14 As long as voting power remains unequally distributed, opaque, and weaponizable, intellectual pluralism will remain an illusion.

Conclusion

Effective Altruism began with a bold goal: to use reason and evidence to help others as effectively as possible. But the way the movement has grown — structurally, culturally, and financially — risks undermining that very mission.

Today, a small group of donors and institutions hold outsized influence over what counts as “effective”, who gets funded, and which ideas gain traction. Criticism is welcomed in theory but often filtered in practice — especially when it challenges core power dynamics. Systems like the karma-based voting structure reward reputational conformity and make it easy to suppress dissent without ever having to engage it.

If EA wants to improve its impact, it must also improve its internal structures. That means more democratic governance, more funding independence, and more systems designed for power sharing.

The question isn’t just how much good we can do, but also who gets to decide what good looks like.

A huge thanks to Maxim Vandaele for helping with this post. All opinions and mistakes are my own.

For more information on this dynamic, I recommend the excellent “Billionaire Philantropy” series by philosopher David Thorstad.

Although I did once win a €60 prize in 2020, which is the exception that proves the rule.

Arguably once, though I wasn’t specifically asked, it was more like an open call. Almost everyone there gave a talk, and I was at the end when most people had already left. I ended up giving my talk to, like, four people. Not sure if that counts.

I guess it depends on what you consider “similar”. So for example, I have been accepted to EA conferences, but not for fellowships. And I have had video-calls with low rank members of EA, but not with the EA higher ups.

E.g. starting and running EA Ghent.

And I’m still not learning my lesson.

As Benjamin Soskis writes:

The main tension to the [effective altruist] movement, as I see it, is one that many movements deal with. A movement that was primarily fueled by regular people – and their passions, and interests, and different kinds of provenance – attracted a number of very wealthy funders [and came to be driven by] the funding decisions, and sometimes just the public identities, of people like SBF and … a few others.

I argue that Effective Altruism is a consequence, form, and facilitator of capitalism.

As David Thorstad writes:

Philanthropic movements such as effective altruism, funded by wealthy Silicon Valley donors, promote many of the same views and practices that made their donors successful as solutions to global problems. For example, here are some views that effective altruists share with Silicon Valley:

(1) Progress in artificial intelligence is the most transformative development facing humanity today, and possibly the most transformative development in human history.

(2) Long-shot investments are worth funding because they sometimes produce outlandish returns.

(3) Data- and technology-driven solutions are to be preferred when possible.

(4) Small teams of highly-trained individuals are well-suited to making disruptive breakthroughs on major problems.

(5) It is not always necessary to make an extensive and detailed study of competing perspectives and approaches before setting out to solve problems in a new way.

These views are popular in Silicon Valley for a reason: they have served technology entrepreneurs well, helping them to become wealthy and bring genuine progress and change within many sectors of society. Now, the question is whether these views will serve other problems in society equally well.

We might be seeing an example of this in EAs relationship with socialism. They tend to think this is a philosophy that intelligent people don’t taken seriously. For example:

One example I can think of with regards to people "graduating" from philosophies is the idea that people can graduate out of arguably "adolescent" political philosophies like libertarianism and socialism.

Despite people in EA thinking of socialism as an "adolescent" political philosophy, actual political philosophers who study this for a living are mostly socialists (socialism 59%, capitalism 27%, other 14%).

Within EA, advocating for socialism gets equated to advocating for a command economy. For example: this EA forum post on socialism got mostly disagreement votes, and, despite not advocating for (or even mentioning) command economies or planned economies, the most upvoted/“agree-voted” comments are those saying command economies are bad.

Suffice to say, if we look at the socialist public figures, both the politicians (e.g. Bernie Sanders, AOC, Jeremy Corbyn etc) and the public intellectuals (e.g. Naomi Klein, Richard Wolff, most humanities professors etc) clearly advocate for a socialist future that doesn’t include a command economy.

To this day, socialist ideas and speakers are generally avoided in EA, even at conferences where very controversial speakers are invited. Those who point this discrepancy out tend to get down-voted.

per “strong” vote, technically, but same difference.

And those are not the only examples. The central directory of people in the EA movement was recently replaced with a system that sorts people by karma.

A counterargument could be that this decreases reliance on moderators, which makes the forum more democratic. I disagree: moderation is public while voting is anonymous so voters can’t be held accountable. Moderation would be more authoritarian than votes if the votes were equal, but they aren’t. If one’s really concerned about authoritarian moderators then we could easily implement a mechanism where the moderators are democratically selected each year. More importantly, the moderation team has a different role than the voters. The moderation is there to police the EAF norms — respectful language, no insults, etc — while the voters affect the substance, the opinions, etc. You can get away with a lot on the forum without being banned, as long as you use the proper form. However, the same cannot be said for the viewpoints/opinions expressed, which, as mentioned before, certain people can hide from the frontpage with quick clicks of a button. Even if you’re still convinced that giving some people more voting power is the way to go, we could easily implement a mechanism where e.g., people can vote on which users get more voting power this year (instead of giving the popular and the karma farmers all the voting power).

Things have slightly improved since the splitting up of “votes” and “agreement votes” but it’s still not great. Worse, anytime you suggest the system should change, people with a lot of voting power downvote you. I’ve made this obvious mistake.

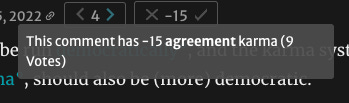

Since we aren’t allowed see the distribution I actually decided to document it for a while to see it for myself. When the suggestion had three votes it had positive agreement karma, but when I returned at five votes it had negative:

Here’s how the karma evolved:

Observe that the downvotes contain a lot more voting weight than the upvotes. It seems like people with more voting power use that power to make sure they don't lose it. The system protects itself.

good article! always disliked the " higher & lower " EA concept.

EA is about improving the world the most. That is a consequentialist goal.

Ideas are debated on merit not based on majority vote. I don't think Democracy is of particular importance here?

Nor is treating all opinions as equally valuable a goal. Some opinions are more correct than others. That's why they have the karma system.

Personally, I like this direction. It is rare and valuable and it is should be protected.